Displaced persons from both sides of the Civil War were arriving to the West in droves, as were deserters, the walking wounded and the downcast limbless. With them, mostly came hope, but also, with some, came the cheapness of life. Two years of bloody strife had whittled away the inherent kindness of many ordinary folk, who remained generally good in heart but had developed an untrusting character as a safeguard. But to others the unbridled, unashamed butchery of this caustic war between cousins just compounded their already miserable existence. So while some rode west in rickety covered wagons in search of hope to escape the horrors of war, others arrived to reap more horror from those desperate masses of hope. In 1862, many of these hopefuls came also for gold. And as these wretched white hordes emerged onto the Great Plains, inevitably shoving away the longstanding native tribes further and further in front of them, so too came the trials of the Indian Wars. The West was destined to change forever. Geography often confused people as to where exactly the Civil War was being fought. While place names such as Vicksburg, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg gave pitiable prominence to the east, lesser known and more clandestine battles were fought elsewhere, with less bloodshed but with more guile, and not always south of the Mason-Dixon line. Without access to gold, not only was the South unable to finance its war, but its Confederate paper currency would be rendered worthless. Despite early victories at Manassas some in the South had lost morale. Confidence in the army and politicians was fading as the appalling casualty lists were made public and their wounded walked home and the dead lay rotting in the fields. Farms had been left untilled and cattle barren as men were drafted into the fight. There was no foreign aid since the South had little worth to call upon apart from its people. The only thing that could save the South, except for a catastrophic military failure in the North, was gold. So along the overland trails went men seeking ways to fetch that gold South, hidden in open sight amongst the throngs crossing the Great Plains, or clandestinely riding along with Minnesotans crossing the Dakotas. A few even went north from Texas.

Displaced persons from both sides of the Civil War were arriving to the West in droves, as were deserters, the walking wounded and the downcast limbless. With them, mostly came hope, but also, with some, came the cheapness of life. Two years of bloody strife had whittled away the inherent kindness of many ordinary folk, who remained generally good in heart but had developed an untrusting character as a safeguard. But to others the unbridled, unashamed butchery of this caustic war between cousins just compounded their already miserable existence. So while some rode west in rickety covered wagons in search of hope to escape the horrors of war, others arrived to reap more horror from those desperate masses of hope. In 1862, many of these hopefuls came also for gold. And as these wretched white hordes emerged onto the Great Plains, inevitably shoving away the longstanding native tribes further and further in front of them, so too came the trials of the Indian Wars. The West was destined to change forever. Geography often confused people as to where exactly the Civil War was being fought. While place names such as Vicksburg, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg gave pitiable prominence to the east, lesser known and more clandestine battles were fought elsewhere, with less bloodshed but with more guile, and not always south of the Mason-Dixon line. Without access to gold, not only was the South unable to finance its war, but its Confederate paper currency would be rendered worthless. Despite early victories at Manassas some in the South had lost morale. Confidence in the army and politicians was fading as the appalling casualty lists were made public and their wounded walked home and the dead lay rotting in the fields. Farms had been left untilled and cattle barren as men were drafted into the fight. There was no foreign aid since the South had little worth to call upon apart from its people. The only thing that could save the South, except for a catastrophic military failure in the North, was gold. So along the overland trails went men seeking ways to fetch that gold South, hidden in open sight amongst the throngs crossing the Great Plains, or clandestinely riding along with Minnesotans crossing the Dakotas. A few even went north from Texas.

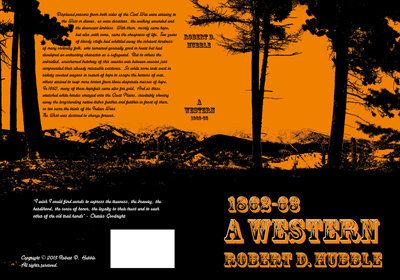

A Western: 1862-63

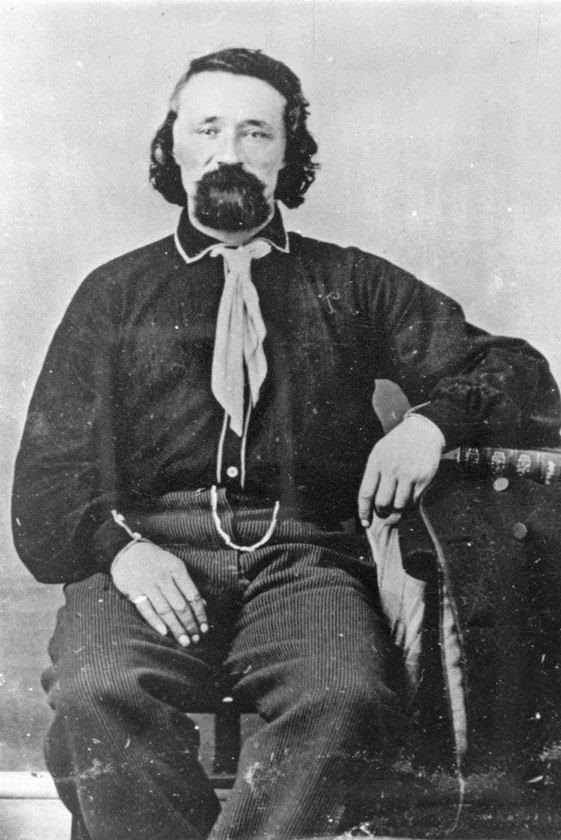

The Grant-Kohrs Ranch was once the headquarters of a 10 million acre cattle empire, established by a Canadian Métis fur trader, John Francis Grant, in 1862 along the banks of the Clark Fork river, at what was then near the eastern boundary of Washington Territory.  Grant had already been using the valley to graze his cattle since 1857, making money trading cattle with emigrants arriving along the Oregon Trail, getting two poor, footsore cows in exchange for one good one and then fattening up the poorer cows on the lush grasses along the Clark Fork, before shipping 400 head to Sacramento, California in 1859.

Grant had already been using the valley to graze his cattle since 1857, making money trading cattle with emigrants arriving along the Oregon Trail, getting two poor, footsore cows in exchange for one good one and then fattening up the poorer cows on the lush grasses along the Clark Fork, before shipping 400 head to Sacramento, California in 1859.

Grant's life, and his legacy to Montana, is worthy of further recognition, and certainly of further reading. Two books I found invaluable, dictated by Grant to his wife, Clotilde Bruneau Grant:

Very Close to Trouble: The Johnny Grant Memoir, Edited by Lyndel Meikle

Son of the Fur Trade: The Memoirs of Johnny Grant, Edited by Gerhard J. Ens

Bitterroot Valley Cabin - Raspberry Pines, Victor, Montana